The European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) 5th Vaccine Conference will hear that the risks of failing to vaccinate children may extend far beyond one specific vaccine, although currently the most urgent problem to address is the resurgence of measles.

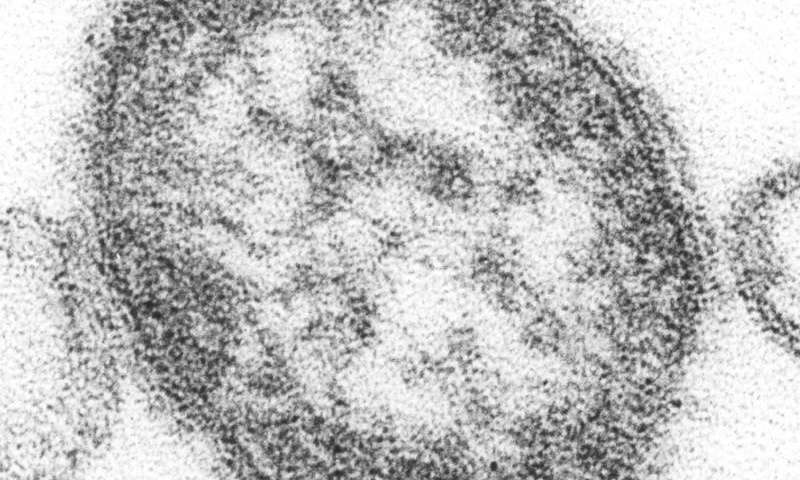

Measles, a highly contagious infectious disease, is serious, causing fever, rash and other symptoms in most children and complications including pneumonia and brain inflammation. In 2018, across the globe measles killed approximately 1 in every 75 children infected with the virus, leading to over 100,000 deaths.

Furthermore, research by Assistant Professor Michael Mina, MD of Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA and colleagues from his own and other groups suggests that infection with measles in unvaccinated children increases their risk of other, subsequent severe, non-measles infectious diseases in the 2-3 years following infection. Thus, after surviving measles, children may fall ill or die from other infections which they previously developed immunity to, but this immunity was erased by the measles virus.

This observation, backed by numerous studies (with the mechanism still being investigated) shows that when measles virus infects a person, it primarily infects a large proportion of the memory cells of the immune system. This results in so called immune-amnesia, whereby the immune system cannot remember some of the diseases it has fought in the past, thus exposing children to re-infection with these other diseases.

These findings would help explain the mysterious large drops in mortality of up to 50% following the introduction of measles vaccinations, even though prior to vaccines measles was usually associated with much less than 50% of childhood deaths. This has gone unnoticed in previous years because clinicians would not, for example, link a death from another infectious disease back to a measles infection that that child may have had two years earlier and that wiped away the child’s immune memory for the other infecting pathogen.

“Prior to vaccination, measles infected nearly everyone. Because we now think that measles infections may erase pre-existing immune memory, by preventing measles infection through vaccination, we prevent future infection with other infectious diseases allowed back into the body by the damage done by measles,” explains Dr. Mina. “The epidemiological data from the UK, USA and Denmark shows that measles causes children to be at a heightened risk of infectious disease mortality from other non-measles infections for approximately 2-3 years.”

He continues: “Prior to vaccination, the incidence of measles from year to year could explain almost all of the variation in non-measles infectious disease deaths that occurred over multiple decades. Altogether, this suggests that measles may have been associated with as much as half of all childhood deaths due to infectious diseases prior to vaccination, and thus explaining the mysterious large drops in mortality seen following introduction of the vaccine.”

He adds: “It may be that the only way for a child to recover from this immune-amnesia is if their memory cells ‘relearn’ how to recognise and defend against diseases they had known before, and they can do this through re-exposure to the pathogen or by re-vaccination against that particular infection.”

However, it is this re-exposure to the other pathogens that pose the long-term risks following a measles infection. A recent epidemiological study led by Dr. Mina’s colleague, Dr. Rik de Swart of the Department of Virosciences at Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, Netherlands looked at the clinical outcomes of over 2,000 children infected with measles in the UK (see link below). In that study, they found that children were significantly more likely to require physician visits and had higher rates of antibiotic prescriptions for 2-5 years following measles. To mitigate these long-term effects, Dr. Mina suggests “It might be reasonable to consider re-vaccination with other childhood vaccines following measles infection.” However, he adds that “because many children who are infected with measles generally have not been vaccinated, whether because of [parental] refusal or are in settings that do not have access to vaccinations in the first place, this may not always be a viable option.”

Thus—probably the most important conclusion of these fascinating studies is that prevention of measles by vaccination is crucial and high vaccination coverage is a fundamental step nowadays. However, in this symposium, Helen Johnson, Expert in Mathematical Modelling at the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) Solna, Sweden and Dr. Takis Panagiotopoulos of the National School of Public Health, Athens, Greece, will highlight that even when contemporary vaccination coverage is high, risk of infection may be concentrated in certain groups. Analysing data from Greece, they say that this heightened risk can be associated with age (low vaccine coverage from previous years) or social aspects (for example, barriers to access for the Roma population, and vaccine hesitancy for healthcare workers or other opinion groups).

The dangers of healthcare workers not being vaccinated are clearly highlighted by these data. “The risk of being infected, and of onwards transmission, is associated with the way people come into contact,” explains Johnson. “Although only approximately 4% of cases were in healthcare workers, an individual case in this group was far more likely than any other to cause five or more secondary cases. In contrast, approximately 30% of cases were in Roma children aged 4 years and under, but each of these children caused, on average, only around one secondary infection.”

Even if vaccination rates nationwide approach 95%, pockets of susceptible unvaccinated people, such as the Roma population or healthcare workers, may make outbreaks not only more likely but also considerably larger than would be expected from assessments of vaccination coverage alone. “The results highlight the imperative of maintaining high vaccination coverage at all subnational levels and in all population groups,” explains Johnson.

Data from ECDC show that a large epidemic of measles has affected the EU/EEA in the past three years, with 47,690 cases reported between 1 January 2016 and 30 June 2019. Only eight countries—Romania (14,712 cases), Italy (10,439), France (5,812), Greece (3,288 c), United Kingdom (2,412), Germany (2,240), Poland (1,874) and Bulgaria (1,295)—were responsible for 88% of the cases in this period, but multiple cases occurred in each of the 30 countries that report data to ECDC.

The burden of measles in the EU/EEA is particularly high among infants and adults, the groups at the greatest risk of complications following infection. Notification rates are much higher in infants and children under 5 years than older age groups, however, a large proportion (39%) of cases during this period occurred in adults aged 20 years and above, reflecting immunity gaps due to historic failures to vaccinate in many countries. “Low uptake of vaccine in certain groups means that, even in countries with very high rates of vaccination coverage, re-establishment of measles is a concerning reality. It is tragic and unacceptable that children and adults continue to die from complications of measles, when safe and effective vaccines are readily available,” concludes Johnson.

This ESCMID 5th Vaccines Congress, which will cover multiple vaccine-preventable diseases is taking place just one week after WHO announced that four European countries: the UK, Albania, Czech Republic and Greece: had all lost their previous ‘measles-free’ status due to confirmed endemic transmission in all four.

“Incidence of measles in the European Region increased in 2018 compared to previous years, and continues to escalate in 2019,” says Dr. Patrick O’Connor, Team Lead, Accelerated Disease Control Vaccine Preventable Diseases and Immunization for the WHO-EURO region, who is also speaking at this symposium.

He concludes: “Elimination of both measles and rubella is a priority goal that all countries of the WHO European Region have firmly committed to achieve. WHO urges health authorities to use every opportunity to reach children with routine vaccination, as well as to identify and close immunity gaps in adolescent and adult populations.”

Source: Read Full Article