A new study from the University of Oxford shows that people who hold coronavirus conspiracy beliefs are less likely to comply with social distancing guidelines or take-up future vaccines.

The research, led by clinical psychologists at the University of Oxford and published today in the journal Psychological Medicine, indicates that a disconcertingly high number of adults in England do not agree with the scientific and governmental consensus on the coronavirus pandemic. The findings indicated that:

- 60% of adults believe to some extent that the government is misleading the public about the cause of the virus

- 40% believe to some extent the spread of the virus is a deliberate attempt by powerful people to gain control

- 20% believe to some extent that the virus is a hoax

From 4 to 11 May 2020, 2,500 adults, representative of the English population for age, gender, region, and income, took part in the Oxford Coronavirus Explanations, Attitudes, and Narratives Survey (OCEANS). Results indicate that half of the nation is excessively mistrustful and that this reduces the following of government coronavirus guidance.

Daniel Freeman, Professor of Clinical Psychology, University of Oxford, Consultant Clinical Psychologist, Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, and study lead, said: ‘Our study indicates that coronavirus conspiracy beliefs matter. Those who believe in conspiracy theories are less likely to follow government guidance, for example, staying home, not meeting with people outside their household, or staying 2m apart from other people when outside. Those who believe in conspiracy theories also say that they are less likely to accept a vaccination, take a diagnostic test, or wear a facemask.’

Guidelines are only effective if the majority of people use them. This pandemic requires a unified response. However the high prevalence of conspiracy beliefs, and low level of trust in institutions, may impede the response to this crisis. The figures suggest a breakdown of trust between political and scientific leadership and a significant proportion of the English population.

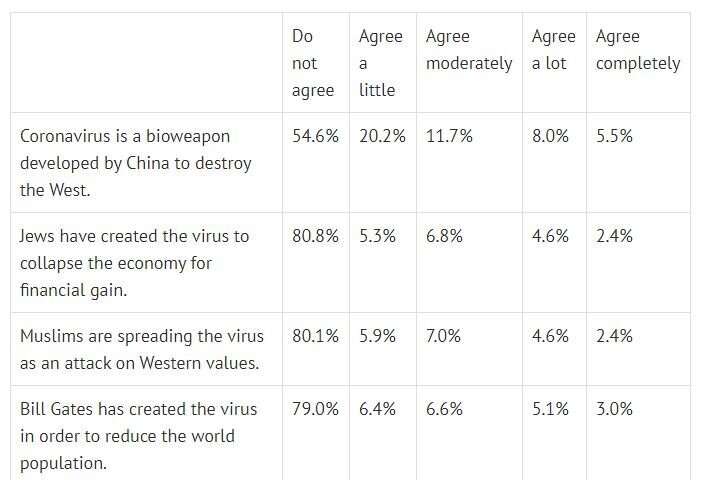

Other beliefs endorsed by a significant minority include (further examples available in the paper):

Professor Freeman continues, ‘There is a fracture: most people largely accept official COVID-19 explanations and guidance; a significant minority do not. The potential consequences, however, affect us all. The details of the conspiracy theories differ, and can even be contradictory, but there is a prevailing attitude of deep suspicion. The epidemic has all the necessary ingredients for the growth of conspiracy theories, including sustained threat, exposure of vulnerabilities, and enforced change. The new conspiracy ideas have largely built on previous prejudices and conspiracy theories. The beliefs look to be corrosive to our necessary collective response to the crisis. In the wake of the epidemic, mistrust looks to have become mainstream.’

Dr Sinéad Lambe, Clinical Psychologist, observed, ‘Conspiracy thinking is not isolated to the fringes of society and likely reflects a growing distrust in the government and institutions. Conspiracy beliefs arguably travel further and faster than ever before. Our survey indicates that people who hold such beliefs share them; social media provides a ready-made platform.’

Source: Read Full Article