"Friendship, like most relationships, requires learning and understanding. If as children, we know of the qualities that make a good friend, we will develop the right discernment and know how to nurture these qualities in ourselves."

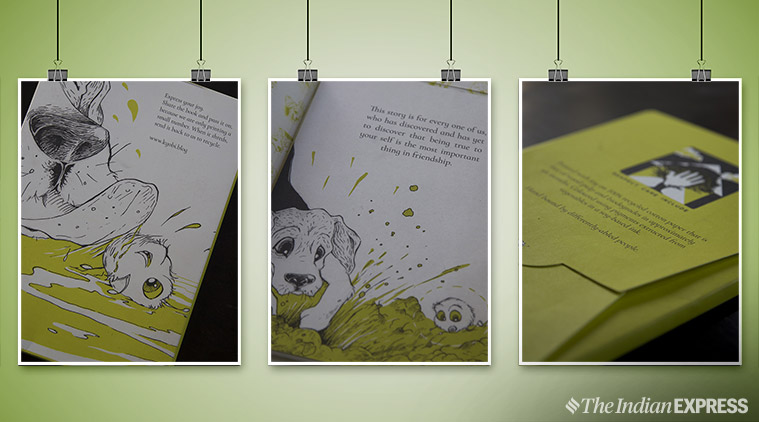

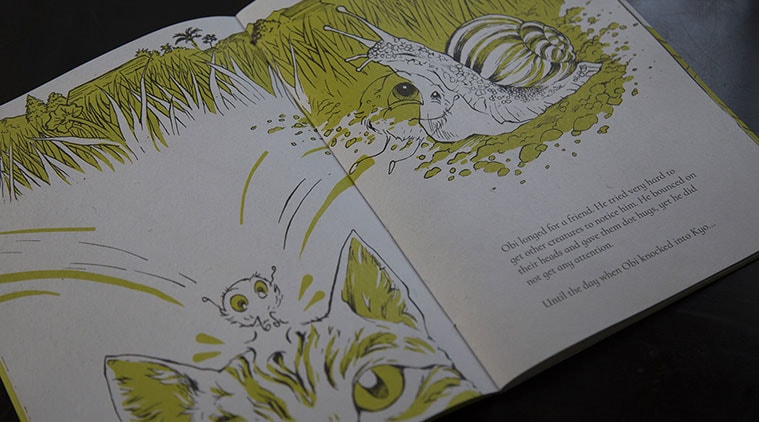

Neha Mundhra’s sustainable illustrated children’s book explores themes of friendship and self-awareness told through Kyo and Obi, a beagle and a mote of dust. She talks to us about the book and printing it on recycled cotton paper, free of wood pulp and getting it hand-stitched by the differently-abled.

What prompted Kyo and Obi?

I wished that growing up, I had a better understanding of the mind and its influence on behaviour. We adults have our own lessons to learn, and we don’t always have the answers. I think it is important not to have children rely on us blindly as examples, but instead speak to them of ways in which they can connect with themselves, and ask the right questions. I wanted to share what I had understood about the importance of developing a healthy relationship with oneself. Kyo and Obi is a story about discovering the joy of self-acceptance through self-observation. Through the polarity of the characters in Kyo and Obi, I explore our notions about similarity in togetherness and journey from an undeveloped identity to a mature, accepting sense of self. Life’s lessons and hard knocks can really diminish self-acceptance, yet it is an essential quality to retain—a quality that is evident in people that live their joy. I wanted to offer children a roadmap to it.

What has been the reaction to the story from kids, about the friendship between a dot and a dog?

I have been told that young children are amazed and delighted by the idea of personifying a dot. It helps that Divya George, the illustrator for Kyo and Obi, has created beautiful and detailed two-page spread illustrations. A 16-year-old boy with learning difficulties found the book very creative; he was interested in finding out how a dot can feel and communicate. He wanted to know if the story was real or imagined.

I was aware, from the start, that a dot would fascinate children — I too was fascinated by dots as a child. The original inspiration for Obi, the dot, came from dust particles, little dots that share our surroundings, yet are invisible till seen. I chose a mote of dust, because I needed the protagonist who would go on an inward journey to be ordinary and without human attachment, to give children the imaginative freedom to explore the inner world with him. It is also refreshing to move away from a dog being typecast as man’s best friend.

Do they relate to the larger message of being yourself and learning to be comfortable in your skin?

Adults and teenagers are appreciating the message in the book. It is harder to explain to younger children, who still rely on adults to comprehend the world. Much of the explanation depends on the parent’s inference, and on the conversations a parent is used to having with the child. A mother from California shared that Kyo and Obi allowed her to have a conversation with her four-year-old that she would not otherwise have had. I think to understand the importance of self-acceptance you need to feel the dissonance that gets created in the mind, when life’s uncertainties threaten the identity that you hold on to.

It is very rare to feel the need for self-acceptance till you haven’t faced rejection, sorrow or disenchantment. This is not a dreary viewpoint; it is simply a part of personal and emotional development that we all experience at some point, in some degree. That’s why I think my book resonates with a certain type of adult. For younger children, the book may offer an example of how to work on developing self-acceptance, or it might be a cue to mindfulness when circumstances are challenging.

How important is it to talk about friendships for a younger audience?

I think it is important to speak about the qualities that make a good friend. Friendship, like most relationships, requires learning and understanding. If as children, we know of the qualities that make a good friend, we will develop the right discernment and know how to nurture these qualities in ourselves.

In friendships that are established on compassion, respect and acceptance, patterns of the relationship can be modified consciously. Both individuals can make space to nourish these qualities and therefore to support each other’s growth.

Friendship is a chance occurrence, and yet for a significant part of our lives it is more influential than the relationships we are born into. We must know how to choose our friends, and we must learn how to be a good friend. It is important to have this conversation first with oneself, and then with children.

Your book is a green initiative, made with recycled paper and using natural pigments. What inspired this and are there other examples of books like this?

I make conscious but realistic choices in what I consume. The more I researched, the more convinced I was that I wanted to reduce the environmental impact of the book. I also find great solace in being surrounded by trees, and using paper made of wood pulp was out of question, unless it was fully recycled.

In the middle of my search for an environmentally committed publishing partner, I went to hear a panel discussion on sustainable fashion. There, I chanced upon Dr Bosco Henriques, who has a doctorate in molecular biology, and is the founder of a company that specialises in natural pigments and dyes. I asked a friend who was on the panel to get me his business card. Dr Henriques was extremely patient in answering my many questions. He helped give direction to my efforts, and he shared the contacts of my production partner, Punarbhavaa, who have developed processes with a commendable pledge to the environment.

Punarbhavaa has made the paper for this book from waste and recycled cotton fibre, in a production facility that is largely solar-powered. The water used in printing is sourced from borewells that are connected to a rainwater harvesting system, and the inks applied are soy-based with colours extracted from vegetables. While soy inks are not free of hydrocarbon solvents, they contain less petroleum-based resins than traditional inks. If ever there is a second book, my attempt will be to go a step further and use ink that does not emit volatile organic compounds and add to the stress on the ozone layer. There is a company in India, started by engineers from IIT, that manufactures such ink, but despite my attempts, I could not reach them for Kyo and Obi. My checklist was long, and I am happy that Kyo and Obi is a product of sincere, committed effort.

How long did it take to produce?

From story to product, the book has taken two years to produce, and it has allowed me to live with the joy that comes with commitment, care, respect, and the long chain of human connections and support. Kyo and Obi costs significantly more than a standard book, almost four times more, yet it has been worth it for all of us who worked on it together. The strong focus on design and sustainability has made the book unique in the marketplace. There are titles that are hand-bound and printed on hand-made paper, and a few that have been produced using soy inks. However, in my visit to bookstores in India and in California, I did not come across any books that are made of recycled cotton paper, are hand-stitched, and are printed with soy inks.

It’s also hand-stitched by the differently-abled. How did that collaboration happen?

When I had just begun writing the story, I decided that the story and the book production must stay true to a set of values. I wanted something to hold this entire initiative together. Respect, Care, and Include are the values that resonate most with me. I have even shared them on the back cover of the book, in a symbol that was created by Paul Rodrigues, a friend, and multi-talented artist and furniture designer, who lives in Goa. These values are the reason why I had the book hand-stitched by differently-abled people. While I was in conversation with Punarbhavaa, I asked if they knew of anyone who could undertake this task. I got lucky, because they outsource some of their work to an organisation that employs people with disabilities for stapling, gluing and simple stitching.

Gluing and stapling were not my first choice, because of their environmental implications, which made stitching the best option, especially since Punarbhavaa could supply the recycled cotton thread that we have used. The challenge was in the style of stitching; I wanted to retain the aesthetic of the design and artwork, and yet had to be conscious that we were working with people who were not necessarily trained or able to take on very complex styles of stitching and binding. Binding by itself is an old art, it is as old as books are. After a month of research and trials we decided to use the long-stitch in two parallel lines on the spine of the book.

Did your blog come first or the book? What’s the purpose of the blog?

There’s a book behind this blog; that’s the tagline that you will find on kyobi.blog. The book did come first, and it is my first book. I am using the blog as an extension of the book to speak about all things related to the theme and making of the book. Theme, as I have understood it, is not the same as the message in a story—theme includes the principles underlying the message. And for Kyo and Obi, the theme is coexistence and harmony. The blog speaks of anecdotes, observations, and reflections that inspire me, and that are within the periphery of this theme.

Tell us a little about yourself and if you plan to be a full-time author?

I am a content writer. I have been writing for businesses for nearly 18 years. I write because it is my natural form of expression. However, the commitment and focus to produce Kyo and Obi, and the insights that I have shared in the story are because of my regular, daily practice of Vipassana meditation. I sat my first course of Vipassana in 2005, and since then I sit at least one course a year. I meditate every day for an hour in the morning and an hour in the evening; this has been my regular practice for over eight years — it is a part of my lifestyle. This diligence has given me the ability to self-observe in silence, and has enhanced the clarity that comes with growing self-acceptance. When I wrote the story for Kyo and Obi, I felt that the understanding of self-acceptance had begun to surface. I felt ready to talk about it.

Are there any more books coming?

There is another story in draft, one that questions the meaning of kindness. I look at kindness through the perspective of a human child, who is uncertain of what it means and unconvinced by the explanations being given. The child finally understands kindness through his own considerate actions, and his encounter with a being from an endangered species. I have tried to bring forth an existing debate about the preservation of the species, through restrained, legalisation of trade in their eggs. I have not taken a stand, but I have used this situation as background to the child’s exploration of kindness.

At this point, I cannot say if this story will be published in the form of a book. This depends on whether Kyo and Obi finds its readers, because the tone and depth of message is similar in both stories.

What do you think of picture books? Can you mention some favourites?

There are many picture books that conventionally get tagged and placed in the children’s bucket, depriving adults of the depth, inspiration and wonder that they contain. Unless you are a parent committed to giving your child a complete reading experience, it is unlikely that you would come across these books. Apart from interest and circumstances, geography governs access, at least of picture books in the English language.

One of the most touching stories that I have come across is, Cry Heart but Never Break, written by Glen Ringtved. The story is about Death, the truth that we hush up and hide from the most. Glen Ringtved’s sensitive depiction of Death allows us to feel our vulnerability. Then there is Du Iz Tak? with its poetic illustrations and its message of impermanence, illustrated and written by Carson Ellis. And of course, Shel Silverstein’s Missing Piece Meets the Big O, which is about the missing piece’s search for someone, because it feels incomplete, till experience takes it to completeness.

The picture books I like most are simple, creative expressions of reality and its nature. They are stories that awaken, and teach. It is heartening to see the growing support and acknowledgement for these books, within well-curated literature and book festivals. While India lacks public libraries that contain an indexed collection of picture books, there is good initiative being taken by independent bookstore owners and schools. Apart from Tara Books’ beautiful collection of artistically produced books, I have enjoyed two sweet stories, published by Little Latitude: The Party in the Sky by Jane DeSouza, and Prashant Miranda, and If I Lived in a Tree House by Kalpana Subramanian and Prashant Miranda.

Source: Read Full Article