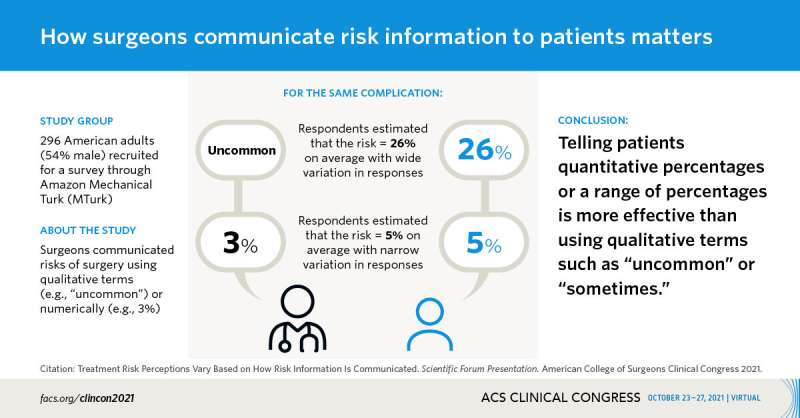

Using quantitative rather than qualitative terms to describe the risks of various treatment options improves communication between surgeons and patients, according to a study presented at the virtual American College of Surgeons (ACS) Clinical Congress 2021.

Based on a survey of American adults, researchers found that using qualitative descriptions of various risks—for example, using terms such as “sometimes” or “uncommon”—led to a wide range of interpretations. In contrast, there was less variance in interpretation when those surveyed were given a risk percentage (for example, a 1 percent risk) or range of risk percentages (for example, 1-5 percent), according to the authors.

Understanding the potential complications of various alternative treatments is important to help patients make informed decisions, said Joshua E. Rosen, MD, MHS, research fellow at the Surgical Outcomes Research Center at the University of Washington, Seattle, and first study author. Patients need accurate information about the types and degrees of risk they face so they can base decisions within the context of what is happening in their lives, Dr. Rosen said.

While the outcomes and quality of life may be very similar when comparing surgery with a course of antibiotics, there are differences in other outcomes that may be important to patients. For example, recovery time associated with an operation could lead to missed work or school days, while antibiotics pose the risk that the problem will not be resolved and may require an operation at a later time. A student with an upcoming exam may prefer to opt for a course of antibiotics rather than surgery first because the recovery time associated with surgery could interfere with taking the exam, Dr. Rosen explained.

“The way surgeons communicate with patients really matters,” Dr. Rosen said. “We need to communicate accurately so that patients can interpret that information within the context of their lives.”

Unfortunately, using qualitative descriptions of risks tends to lead to a wide array of interpretations. For example, those surveyed were given one of three descriptions of the risk of deep space infection after appendicitis surgery:

- 3 percent

- 1-5 percent

- uncommon

Respondents were then asked to characterize the risk of deep space infection after an operation for appendicitis (appendectomy). Those who were told the risk was “uncommon” said they interpreted this term as meaning their chance of getting an infection was, on average, a 26 percent chance, far higher than the point estimate of 3 percent or the range of 1-5 percent.

“Surgeons need to thoughtfully communicate such information because it can affect how patients perceive risks. Our findings advance something all surgeons know they should do by highlighting ways surgeons can do it,” said Joshua M. Liao, MD, MSc, the senior study author. “Surgeons can use our findings to consider when and how to communicate risks using numerical estimates and ranges.”

Findings are communication tools

The study’s findings are intended to be used as tools to help surgeons counsel patients, Dr. Rosen said. Based on these findings, surgeons should:

- Recognize that the way information is communicated affects how patients receive or interpret it.

- Communicate with numbers because it leaves less room for variation in interpretation.

- Use qualitative description of risks only if they are accompanied by numbers.

- Check with patients to assess how well they understand their condition and potential treatment options.

The surveys were conducted among 296 American adults (54 percent were male) recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk). Respondents were asked to estimate the risk of complications (0 to 100 percent) for “a typical patient with appendicitis.” The study used Fligner-Killeen tests for homogeneity of variances to compare the spread in respondents’ estimates based on risk communication language.

Among the 296 respondents, variance in risk estimates was highest for all complications tested when risks were communicated using qualitative descriptors. In addition, variance was generally lower when risks were communicated as point estimates rather than ranges.

A broader effort is underway

Source: Read Full Article