In the same year that Howard Tucker, MD, began practicing neurology, the average loaf of bread cost 13¢, the microwave oven became commercially available, and Jackie Robinson took the field for the Brooklyn Dodgers as the first Black person to play Major League Baseball.

Since 1947, Tucker has witnessed major changes in healthcare, from President Harry S. Truman proposing a national healthcare plan to Congress to the current day, when patients carry their digital records around with them.

Tucker has been a resident of Cleveland Heights, Ohio, since 1922, the year he was born. He is now in his 75th year of practicing neurology and is currently teaching residents and practicing medicine at St. Vincent Charity Medical Center in Cleveland.

Dr Howard Tucker

After graduating high school in 1940, Tucker attended the Ohio State University, where he received his undergraduate and medical degrees. During the Korean War, he served as chief neurologist for the Atlantic fleet at a US Naval Hospital in Philadelphia. Following the war, he completed his residency at the Cleveland Clinic and trained at the Neurological Institute of New York.

Tucker chose to return to Cleveland, where he practiced at the University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center and Hillcrest Hospital for several decades.

Not content with just a medical degree, at the age of 67, Tucker attended Cleveland State University Cleveland Marshall College of Law. In 1989, he received his Juris Doctor degree and passed the Ohio bar examination.

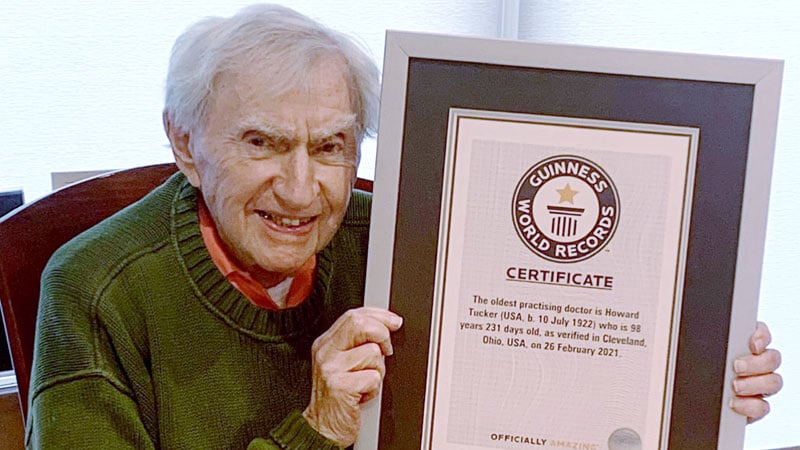

And as if that weren’t enough career accomplishments, Guinness World Records dubbed him the world’s oldest practicing doctor at 98 years and 231 days. Tucker continues to practice into his 100th year. He celebrated his birthday in July.

Medscape recently talked to Tucker about his life’s work in medicine.

Medscape: Why did you choose neurology?

Tucker: Well, I think I was just fascinated with medicine from about the seventh or eighth grade. I chose my specialty because it was a very cerebral one in those days. It was an intellectual pursuit. It was before the CAT scan, and you had to work hard to make a diagnosis. You even had to look at the spinal fluid. You had to look at EEGs, and it was a very detailed history taking.

Medscape: How has neurology changed since you started practicing?

Tucker: The MRI came in, so we don’t have to use spinal taps anymore. Lumbar puncture fluid and EEG aren’t needed as often either. Now we use EEG for convulsive disorders, but rarely when we suspect tumors like we used to. Also, when I was in med school, they said to use Dilaudid; don’t use morphine. And now, you can’t even find Dilaudin in emergency rooms anymore.

Medscape: How has medicine overall changed since you started practicing?

Tucker: Computers have made everything a different specialty.

In the old days, we would see a patient, call the referring doctor, and discuss [the case] with them in a very pleasant way. Now, when you call a doctor, he’ll say to you, “Let me read your note,” and that’s the end of it. He doesn’t want to talk to you. Medicine has changed dramatically.

It used to be a very warm relationship between you and your patients. You looked at your patient, you studied their expressions, and now you look at the screen and very rarely look at the patient.

Medscape: Why do you still enjoy practicing medicine?

Tucker: The challenge, the excitement of patients, and now I’m doing a lot of teaching, and I do love that part too.

I teach neurology to residents and medical students that rotate through. When I retired from the Cleveland Clinic, 2 months of retirement was too much for me, so I went back to St. Vincent. It’s a smaller hospital but still has good residents and good teaching.

Medscape: What lessons do you teach to your residents?

Tucker: I ask my residents and physicians to think through a problem before they look at the CAT scan and imaging studies. Think through it, then you’ll know what questions you want to ask specifically before you even examine the patient, know exactly what you are going to find.

The complete neurological examination, aside from taking the history and checking mental status, is five minutes. You have them walk, check for excessive finger tapping, have them touch their nose, check their reflexes, check their strength — it’s over. That doesn’t take much time if you know what you’re looking for.

Residents say to me all the time,”55-year-old man, CAT scan shows….” I have to say to them, “Slow down. Let’s talk about this first.”

Medscape: What advice do you have for physicians and medical students?

Tucker: Take a very careful history. Know the course of the illness. Make sure you have a diagnosis in your head and, specifically for medical residents, ask questions. You have to be smarter than the patients are, you have to know what to ask.

If someone hits their head on their steering wheel, they don’t know that they’ve lost their sense of smell. You have to ask that specifically, hence why you have to be smarter than they are. Take a careful history before you do imaging studies.

Frankie Rowland is an Atlanta-based freelance writer.

For more news, follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.

Source: Read Full Article