Researchers at the University of São Paulo (USP) in Brazil have demonstrated for the first time that in COVID-19 patients an immune mechanism known as the inflammasome participates in activation of the inflammatory process that can damage several organs and even lead to death.

An article reporting the findings of the study, which was supported by FAPESP, has just been published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine. According to the authors, the findings support the use of inflammasome activation both as a marker of disease prognosis, helping medical teams identify high-risk patients at an early stage, and as a potential therapeutic target in severe COVID-19.

“Drugs already approved for human use are capable of inhibiting inflammasome activation. These drugs can now be tested in the context of infection by SARS-CoV-2,” Dario Zamboni, a professor at USP’s Ribeirão Preto Medical School (FMRP-USP) and principal investigator for the study, told Agência FAPESP.

Almost all immune cells are equipped with the protein complex that constitutes the inflammasome, he explained. When one of these proteins identifies a sign of danger, such as a viral or bacterial particle, for example, the defense machinery is activated. As a result, the cell enters a process of programmed death (a type of inflammatory death called pyroptosis) and releases into the bloodstream signaling molecules called cytokines that attract to the site a veritable army of white blood cells. This is the onset of an inflammatory response that is ultimately designed to destruct the potential threat to the organism.

“The response to various pathogens involves inflammasome activation, and most of the time this blocks the infection and protects the organism. However, in some COVID-19 patients, the defense system appears to be overactivated, and we’re now trying to understand why this happens,” Zamboni said.

The involvement of this immune mechanism in the systemic inflammation that is characteristic of severe COVID-19 has been studied by scientists in several countries over the past few months. The Ribeirão Preto group is the first to demonstrate the activation of a specific type of inflammasome in response to infection by SARS-CoV-2 in patients.

“It’s important to recall that there’s more than one kind of inflammasome. What varies is the protein responsible for mediating activation of the protein complex,” Zamboni said. “We observed the presence of the inflammasome mediated by NLRP3, one of the most common and well-studied proteins. Other kinds may also participate in the response to SARS-CoV-2.”

Three angles of investigation

The conclusions presented in the article were based on three sets of experiments. The first involved immune cells from healthy donors infected with the novel coronavirus in the laboratory. The only white blood cells used in the experiment were monocytes.

“The viral dose administered to the culture is considered low, roughly one virus per cell. Even so, 75% of the monocytes died after 24 hours, evidencing the virus’s destructive potential,” Zamboni said.

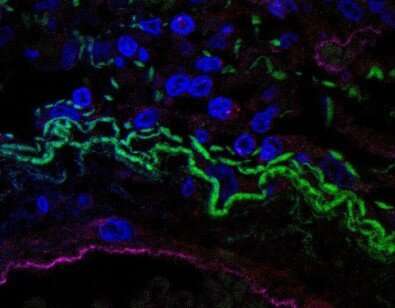

The presence of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) in the culture medium told the researchers that the cells were dying by pyroptosis: LDH is released when the cell membrane is breached and cellular contents escape into the bloodstream, a phenomenon typical of inflammatory cell death. The presence of cytokines IL-18 (interleukin-18) and IL-1β (interleukin-1 beta) suggested that this “serial cellular suicide” was associated with activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, which was confirmed by analysis under the microscope.

“When this kind of inflammasome is activated, the proteins that form the complex, and are normally distributed throughout the cytoplasm, cluster together in what are called puncta, or specks, which can be observed under a microscope,” Zamboni said. “This, in turn, activates caspase-1, the enzyme that ‘processes’ the precursors of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-18 and IL-1β so that they become ‘mature’ and active.”

The second set of experiments involved clinical samples from 124 patients undergoing treatment for moderate or severe COVID-19 between April and July at the general and teaching hospital (“Hospital de Clínicas”) run by FMRP-USP. The results were compared with data from patients hospitalized for other reasons, who served as a control group.

The researchers performed immunoenzymatic tests (based on antigen-antibody reactions) and used molecular probes to confirm that the white blood cells from COVID-19 patients had much larger amounts of IL-18 and active caspase-1 on average.

They observed under the microscope that puncta were more abundant in the immune cells of donors infected by SARS-CoV-2. Statistical analysis showed that the more evidence of inflammasome activation a patient displayed on admission to hospital, the worse the patient’s clinical progression and the higher the probability of death.

The third and last group of experiments used samples of lung tissue obtained during a minimally invasive autopsy procedure from five people who died after being infected by SARS-CoV-2. The analysis evidenced the presence of white blood cells infected by the virus, and puncta characteristic of the NLRP3 inflammasome inside the cells.

Next steps

The assays performed to date were supported by FAPESP via a Thematic Project and a Regular Research Grant awarded to Zamboni, who is also a member of the Center for Research on Inflammatory Diseases (CRID), a Research, Innovation and Dissemination Center (RIDC) funded by FAPESP and hosted by FMRP-USP.

The same group of more than 40 researchers is now working to find out whether other kinds of inflammasome are involved in the response to the novel coronavirus and why the pathogen activates this immune mechanism so intensely.

“We’re conducting experiments in which we compare inflammasome activation in response to SARS-CoV-2 and other viruses, such as the H1N1 flu virus,” Zamboni said.

Separately, the scientists are testing the use of a drug to inhibit the NLRP3 inflammasome in patients with severe COVID-19. Promising preliminary results have been published on medRxiv.

Source: Read Full Article