It’s easy to believe that society’s treatment of difficult, violent and criminally mentally ill people has become more humane over time. But that’s not the case. How patients at the end of the 19th century actually felt is difficult to say, but they were at least less exposed to mechanical coercion, according to an NTNU historian.

Given that psychiatric patients in the 1970s could be strapped to a bed for months, how would patients have been treated in the early 1900s? Better—according to Magne Brekke Rabben.

“Although it’s easy to believe that society’s treatment of the difficult, violent and criminally insane has become more humane over time, it turns out that’s not the case,” he says.

Rabben studied the use of coercive measures at two Trondheim institutions—Reitgjerdet Hospital and Trondheim Criminal Asylum (Kriminalasylet) – for his doctoral dissertation titled “Humanity, control and coercion” at NTNU’s Department of Modern History and Society.

The dissertation is part of the “Prison of Madness” project, led by Øyvind Thomassen.

“The treatment at the institutions didn’t develop in a linear fashion, from inhumane treatment to the current standard,” says Rabben. “A lot of debate about what constituted humane treatment took place at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century. The asylums had clear standards. This differed from the coercive measures at Reitgjerdet that had become almost routine in the 1960s and first half of the 1970s, when the institution lost sight of humanity.”

From madhouses to asylums

Psychiatry emerged as a separate field of study at the end of the 18th century.

In Norway, the first asylum was founded in Gaustad near Oslo in 1855. Before that time, difficult psychiatric patients were kept in “madhouses,” small institutions connected to hospitals, town halls or prisons. Psychiatric patients who had been convicted were held in prison.

In 1842, a new penal code was passed which stated that the criminally insane should not be imprisoned. The progressive Mental Illness Act of 1848 stipulated that institutions should provide treatment, have medical leadership and that coercion should be used as little as possible.

“Conditions in Norwegian asylums in the 19th century weren’t all rosy, but inspired by British psychiatrists, the ideology was to use as little coercion as possible, with a ‘no restraint’ ideal. The goal was to help make patients healthier,” says Rabben.

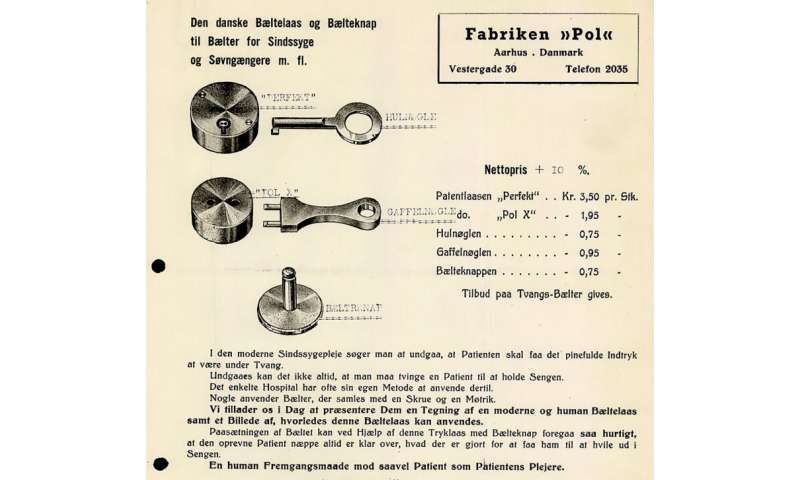

He distinguishes between three types of coercive measures: mechanical coercion (straps and belts), isolation and chemical coercion (sedatives).

Chained to the wall

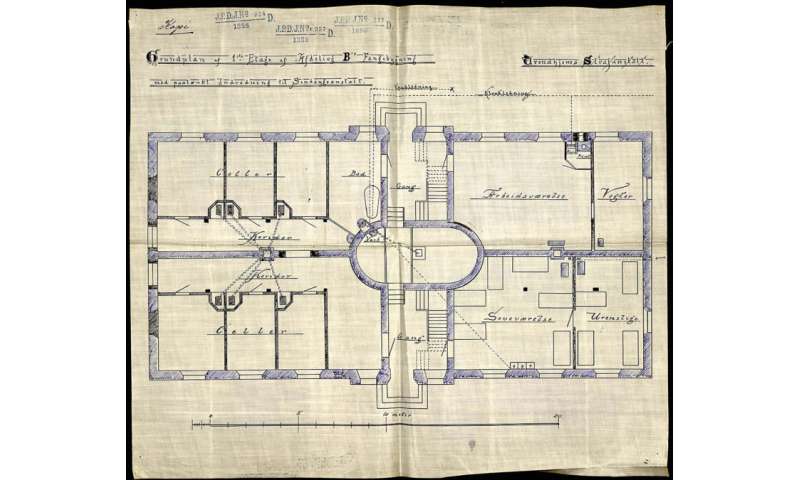

The criminal asylum at Kalvskinnet in Trondheim was the country’s first special institution for dangerous criminals and received a special permit when it was established in 1895. The premises had been a prison, and the rooms were small and cramped with only a small outdoor yard for the 16 patients.

The institution was a cross between prison and asylum. Under the first manager, patients who acted out were simply chained to the wall. The reason given was that they were so dangerous that humane considerations had to give way.

Out with the chains

The chains disappeared with the next manager, Hans Evensen. He was significantly younger and opposed to mechanical coercion. Instead, the most difficult patients were locked up in solitary confinement most of the time. In acute situations, they were sedated. But most patients were not treated that way.

“The patients could work on small projects, be out in the yard, participate in worship services and sleep in shared dormitories. The caregiving staff lived in the same building or in neighboring buildings,” Rabben says.

“It struck me how much care the staff provided for the patients. They tried to solve difficult situations without the use of physical force, but occasionally coercion was used that wouldn’t be tolerated today,” says Rabben.

Rabben’s most important sources of information were Reitgjerdet’s and the Criminal Asylum’s own archives, patient records, ward reports, protocols on coercive use, the Control Commission’s reports, ministry letters and correspondence.

Reitgjerdet broadens its reach

Eventually, the Criminal Asylum could no longer meet the needs as a special institution. In 1923, Reitgjerdet in Trondheim, which had been a hospital for lepers, was put to use. In addition to criminals, the institution was to treat particularly dangerous and difficult male patients.

In the 1920s and 1930s, a perception emerged that the psyche could be influenced through targeted physical treatment methods.

Extreme “treatments” like cardiazol therapy, electroshock and insulin injections were developed to put the patient into an induced coma. The most extreme practice was lobotomy. At Reitgjerdet, 36 patients were lobotomized before the practice was stopped in 1953.

More isolation

As national security institutions, Criminal Asylum and Reitgjerdet patients held a special position in the Norwegian psychiatric institutional landscape. Their use of coercive measures was always much higher than at other psychiatric institutions.

Eventually, isolation began to be seen as more harmful than mechanical coercion. The idea was that it was better to be strapped into a ward where the patient could see and talk to others, than to be locked up alone for long periods.

Medical revolution

Reitgjerdet was intended for about 130 patients, but that number was quickly surpassed. When the Germans seized several asylums during the war, the number of patients at Reitgjerdet rose to almost 300. Occupancy gradually decreased after the war, and in the 1960s a new building was brought into use.

At the end of the 1950s, the use of coercive measures declined sharply. “The psychopharmacological revolution” introduced effective new antipsychotic drugs that worked on the nervous system. The new medicines calmed the wards and made them easier to manage.

Coercion exploded

But starting in 1962-63 a change took place at Reitgjerdet. The use of coercive measures increased sharply and remained at a high level until 1974-75. In the most challenging wards, it became routine to strap patients to their beds at night, sometimes just by one foot. Almost everyone slept in dormitories. It was considered unjustifiable to strap only certain individuals, because they would then be defenseless.

“Many reasons led to the abrupt increase in coercion. In 1963, patients and staff from the closed down Criminal Asylum were transferred to Reitgjerdet. These carers were used to a much higher level of safety and brought a different culture with them. Recruiting competent staff was also difficult. Medical positions remained vacant for years. At times, no one had a nursing education. A large part of the staff was unskilled and didn’t have much experience surrounding the ethical issues of treatment,” says Rabben.

No restrictions on coercion

The historian also points to another reason. In 1961, a new law on mental health care was passed. Unlike before, the law included no provisions on coercive measures.

“The use of coercive measures was considered the doctor’s responsibility. The authorities had great faith that psychiatry ensured humane treatment. In practice, the use of coercive measures was an unregulated area at this time,” says Rabben.

Regulations governing coercion were enacted in 1971.

The Reitgjerdet scandal

Reitgjerdet was subjected to strong criticism after physician Svein Solberg helped a patient escape from Reitgjerdet in 1978 and the press published revelations about the use of coercive measures there.

“It was high time for the reprehensible conditions to come to light. Some patients were strapped down almost around the clock for months on end, or locked in isolation rooms for the same length of time. Many residents were old and harmless and should have been freed or discharged to a regular psychiatric institution. The attitude patients were met with was also criticized,” says Rabben.

The Reitgjerdet scandal implicated the entire system, including the health authorities and politicians who allowed the conditions.

Following a devastating investigation report, Reitgjerdet was closed down in 1987, and the state paid large amounts of restitution to patients.

Regional security departments

Source: Read Full Article