As the COVID-19 pandemic took hold of the world last spring, many nations enacted similar lockdown policies intended to restrict movement and halt transmission—yet some countries fared far better than others.

Newly published research, led by William & Mary undergraduate Morgan Pincombe, analyzes public health disparities among 113 countries in the wake of the pandemic. The findings indicate that failure to account for different economic realities led to contextually inappropriate policy responses that “may exacerbate poverty and cause unnecessary death.”

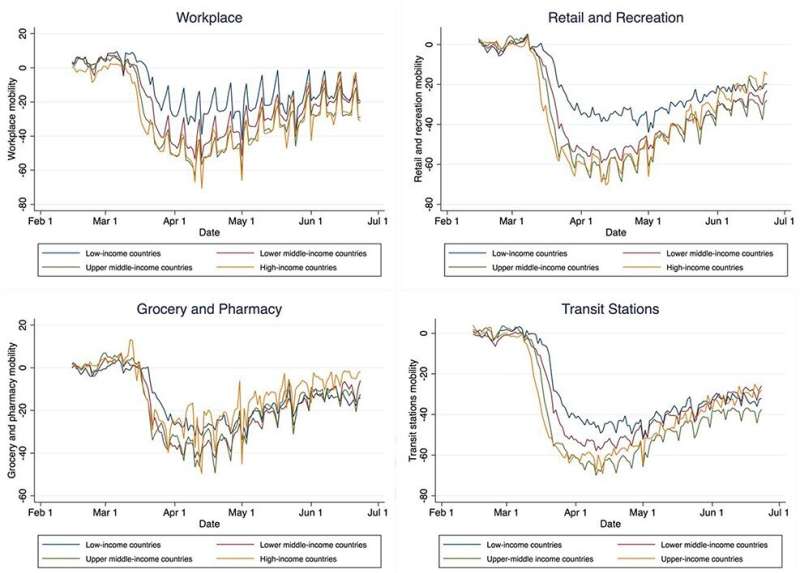

The study involved an analysis of mobility, morbidity, and mortality growth rates across the World Bank’s income group classifications, which revealed that a one-size-fits-all approach to public health policy can have detrimental consequences for low-income countries.

“I wondered if there was a way we could look at emergency response and critique it, so that in the future, we could have some kind of feedback or advice on how to respond to public health emergencies,” Pincombe said. “When we give these international guidelines of “It’s effective to respond to a public health emergency by putting in these policies,” are we really speaking to an audience that’s more high-income, upper-middle income, or is that advice relevant for all countries?”

Even as she was stuck indoors in the United States, international relations and public health major Pincombe couldn’t help but look outward, questioning how the effectiveness of these sweeping rules might differ around the world.

She worked with Carrie Dolan, Director of Ignite at the Global Research Institute and assistant professor of public health at William & Mary, to understand how epidemiological results of containment and closure measures varied across 113 countries. The pair’s research, which is novel in its consideration of income level as a factor of COVID-19 outcomes, earned publication in Health Policy and Planning, a premier scientific journal.

As Pincombe brainstormed how she might use her grant as a James Monroe Scholar to produce meaningful research, unprecedented circumstances both sparked curiosity and cast a sense of responsibility. Once Pincombe identified a few areas of interest, she sought out mentorship from Dolan, whose approach to research she admired based on past experiences.

“I had taken her epidemiology class during my freshman year and really loved the content and also really loved working with her,” Pincombe said. “She was my research advisor there, so when I had this opportunity, I was like “Hey, can I work with you again?'”

Dolan helped her to specify a policy-relevant topic with global implications, encouraging her to develop the work into a journal article instead of the paper she had originally planned. In her role on William & Mary’s Public Health Advisory Team, and through her work on other pandemic-related research, Dolan said she knew these quantitative insights were missing from the policy dialog.

“I think examining the contextual details has been left out of the policy implementation and mitigation measures we have come up with during the pandemic,” Dolan said. “There are a couple of broad, overarching strategies—masking, social distancing, and limiting your mobility—and then those were rolled out across the world without considering how they could be implemented more effectively in some contexts versus others.”

Though the volume of such a task seemed heavy, Dolan also felt excited by the potential to cultivate Pincombe’s skillset and produce meaningful research.

“When Morgan came to me with this idea, there was hardly any data out there,” Dolan said. “I wasn’t sure how we were going to combine it all together. It seemed like an enormous amount of work, but she was willing to put the time and effort in, and it’s important, so I was willing to mentor Morgan in order to make it happen.”

To interpret and understand the results of this project, Pincombe first needed to learn how to build an econometric model and use Stata, a statistical software program, Pincombe relied on guidance and expertise from Dolan and from economics professors Jen Mellor and Ariel BenYishay, but she also sought out external resources.

“She’s very motivated and a self-starter,” Dolan said. “I knew that she would work hard to create a good, high-quality product. The reason that I was willing to take this on was that I knew that even though Morgan had a lot to learn, she would show up and be committed and work hard to do the next steps, so that we would ultimately have a successful project.”

Pincombe’s training prepared her to account for vast amounts of data in the study, studying the effectiveness of movement restrictions and lockdowns in three different ways: mobility, number of cases, and mortality.

“Google had these really cool mobility reports that had anonymous data from cell phones and tracked people’s movement and compared it to the baseline from pre-pandemic,” she said. “We used that to measure, when lockdown policies were put into place, did people move less, or did they move more towards certain things, such as grocery stores and pharmacies?”

The results demonstrated that approaches of containment and closure were more effective in high-income countries than in low-income ones, further suggesting that when guidance fails to account for contextual details—such as economic status—it may exacerbate poverty and death.

“What this work really does is highlight the importance of taking a minute and figuring out how these policies might have worked better if we didn’t roll them out as a one-size-fits-all approach,” Dolan said. “When thinking about policies, you have to think about the audience and their ability to implement what you’re suggesting.”

In some ways, the results confirmed what Dolan and Pincombe hypothesized, but in other ways, the data challenged their assumptions.

“When we were looking at our mortality findings, we would have expected a larger magnitude of difference between the death rates for each income classification, but we see in death, it’s almost identical for each of the income categories,” Dolan said. “I don’t think this is driven by inadequate surveillance or low testing. Instead, I think it’s partly a reflection of the fact that in these resource-constrained countries, these lower-income countries, they tend to report lower mortality overall than the global trend because of other factors such as the weather, the younger population, and less chronic disease. These factors have contributed to fewer cases of COVID-19 and therefore less deaths.”

Adapting to unforeseen circumstances and allowing the data to surprise her, Pincombe said, cultivated personal and professional growth that she can apply to future work experiences—which she hopes take place in the policy arena.

“That’s the research process,” Pincombe said. “As you learn more, as you’re exposed to new information, that changes and shapes the work that you’re doing. Oftentimes, that pushes you to revisit the work, and that creates a better project.”

As Pincombe applies these lessons to her future research endeavors, she will remember the expert mentorship, academic guidance, and peer support that Dolan and the campus community offered her.

“When you’re an undergraduate, it can feel like you have no right to ask people to help you out, but I was very surprised at how willing people were,” Pincombe said. “Take advantage of the expertise and the people you have within your network or that you can reach out to.”

As William & Mary encourages students to pursue thought-provoking, transformative research, Dolan said, it ensures that Pincombe’s story of success is not isolated.

Source: Read Full Article