The coronavirus’ omicron variant starting to barrel across South America is pressuring hospitals whose employees are taking sick leave, leaving facilities understaffed to cope with COVID-19′s third wave.

A major hospital in Bolivia’s largest city stopped admitting new patients due to lack of personnel, and one of Brazil’s most populous states canceled scheduled surgeries for a month. Argentina’s federation of private healthcare providers told the AP it estimates about 15% of its health workers currently have the virus.

The third wave “is affecting the health team a lot, from the cleaning staff to the technicians, with a high percentage of sick people, despite having a complete vaccination schedule,” said Jorge Coronel, president of Argentina’s medical confederation. “While symptoms are mostly mild to moderate, that group needs to be isolated.”

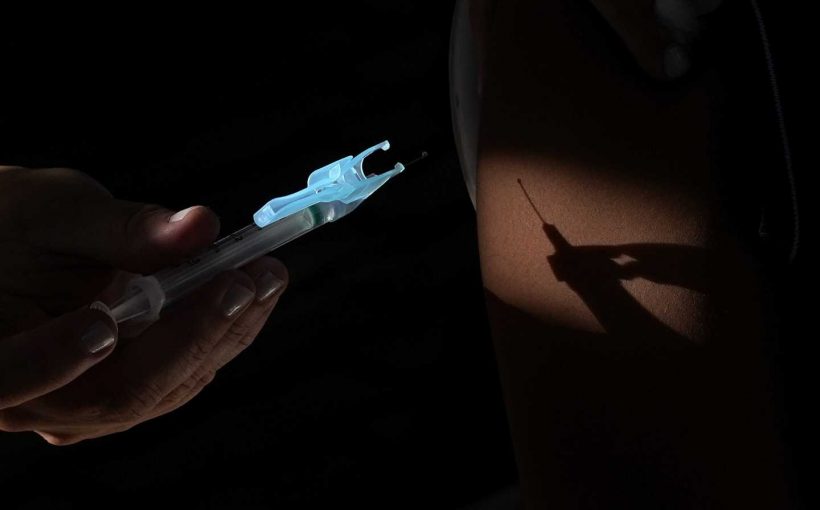

It wasn’t supposed to be this way: South America’s vaccine uptake was eager once shots were available. About two-thirds of its roughly 435 million residents are fully immunized, the highest percentage for any global region, according to Our World in Data. And health workers in Brazil, Bolivia and Argentina have already been receiving booster shots.

But the omicron variant is defying vaccines, sending case numbers surging. Argentina saw an average 112,000 daily confirmed cases in the week through Jan. 16, up from 3,700 a month earlier. Brazil’s health ministry is still recovering from a hack that left coronavirus data incomplete; even so, it shows a jump to an average 69,000 daily cases in the same seven-day period, up 1,900% from the month before.

Omicron spreads even easier than other strains, and is already dominant in many countries—among them, Brazil and some parts of Argentina. It also more easily infects those who have already been vaccinated or infected by earlier versions of the virus. Early studies show omicron is less likely to cause serious diseases than the delta variant, and vaccination and booster shots still offer strong protection against serious illness, hospitalization and death.

Lesser severity leaves South America’s residents loath to give up their long-awaited summer that, so they were told, would mark a return to normality after full vaccination. The enduring pandemic often seems an afterthought to people who are out and about, and don’t glimpse how omicron has started affecting medical staff. Beaches were packed this weekend in Argentina and Brazil.

Matías Fernández Norte, a surgeon at the Hospital de Clínicas in Buenos Aires, told the AP that the high number of professionals on leave has generated “physical and spiritual fatigue, in addition to the stress of dealing with a patient on the edge.”

“You feel like you are living a parallel reality. In the street you meet a world that doesn’t seem to feel the pandemic,” he said. “Sometimes it feels like people have forgotten. Unfortunately, that’s what we feel.”

Brazil’s council of state health secretariats estimates that between 10% and 20% of all professionals in the health network—including doctors, nurses, nurse technicians, ambulance drivers and others in direct contact with patients—have taken sick leave since the last week of 2021.

“We are having trouble making the schedules,” said the council’s director, Carlos Lula.

The press office of Rio de Janeiro state’s health secretariat told the AP that about 5,500 professionals have left their jobs since December. All elective surgeries scheduled in the state health network have been suspended for four weeks. As for urgent care, relocations and overtime are being used as stopgap measures.

“Forty percent of our staff is on sick leave,” Marcia Fernandes Lucas, health secretary for the municipality of Sao Joao de Meriti, in Rio’s metropolitan region, told the AP in her office. “We are able to work with these 60% by redeploying them (between health centers).”

Public hospitals in Bolivia are operating at 50-70% capacity due to the high number of infections among health care workers, according to the Bolivian doctors’ union. In Santa Cruz, the country’s most populous city, the Children’s Hospital is overwhelmed—but less by its number of patients than the amount of staff falling ill, according to Freddy Rojas, its vice director. Last week, the facility stopped admitting new patients.

“There has been a collapse, because we don’t have replacements,” said José Luís Guaman, interim president of the doctors’ union in Santa Cruz.

Such is the risk of medical services grinding to a halt in Argentina’s Buenos Aires province—the country’s most populous—that health workers have been allowed to return to work even if coming into contact with someone infected, provided they are asymptomatic and vaccinated. Other provinces in Argentina are expected to adopt the same rules in the coming days, in line with the health ministry’s recently-issued guidelines.

Similar measures are being enacted by authorities in France and the U.S., where omicron has been putting hospital systems to the test for weeks.

Chile has seen a constant increase in its number of cases, prompting the reactivation of public- and private-sector hospital beds, but so far the country hasn’t experienced hospital overload. Peru has also seen case its numbers rise, but its facilities aren’t yet suffering.

The Pan American Health Organization said Wednesday it expects omicron to become the predominant coronavirus variant in the Americas in the coming week. Ten countries in the region—especially in the Caribbean—didn’t reach the goal set by the World Health Organization to have 40% of citizens fully vaccinated by end-2021.

While a smaller fraction of people develop serious illness from the the highly-transmissible variant, the crush of contagion and resulting strain on hospitals means omicron shouldn’t be underestimated, said Lula, of the Brazilian health secretariat council.

Source: Read Full Article