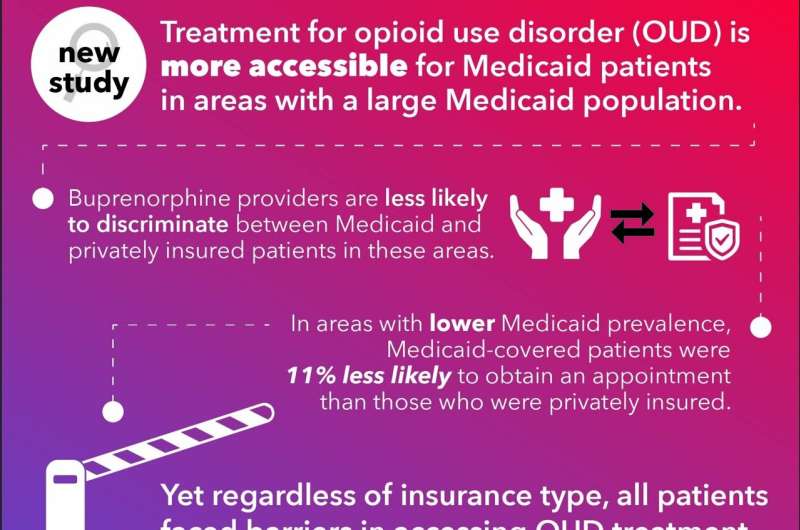

Researchers report that in communities where Medicaid is a more common source of insurance, providers of buprenorphine, an effective treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD), are much less likely to discriminate between Medicaid and privately insured prospective patients, but patients with either type of coverage still face many barriers to obtaining an initial appointment for treatment.

Authors of the study published in Health Services Research used county-level information on Medicaid enrollment combined with randomized field experiment data from 10 states obtained during a previous study. They then used a simulated patient caller or “secret shopper” method to determine how likely buprenorphine treatment providers were to grant an appointment to female callers who identified themselves as being covered either by Medicaid or privately insured.

Investigators from Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s Departments of Pediatrics and Health Policy, Baylor University’s Hankamer School of Business, and RAND Corporation collaborated on the study.

“In areas where Medicaid is a common source of insurance there is effectively no difference in the likelihood of being granted an appointment to obtain a buprenorphine prescription, no matter if the patient had Medicaid coverage or private insurance,” said Michael Richards, MD, Ph.D., MPH, an associate professor at Baylor University.

“But the most striking finding is—for both callers that had private insurance and callers that had Medicaid—just how infrequently they’re able to actually leverage those insurance benefits when it comes to getting an appointment for opioid use disorder. That really speaks to the many serious and substantive access hurdles these individuals have to clear.”

According to a recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics, there were an estimated 100,306 drug overdose deaths in the United States during the 12-month period ending in April 2021, an increase of 28.5% from the 78,056 deaths during the same period the year before. Of that number, the estimated overdose deaths from opioids increased to 75,673, up from 56,064 the year before.

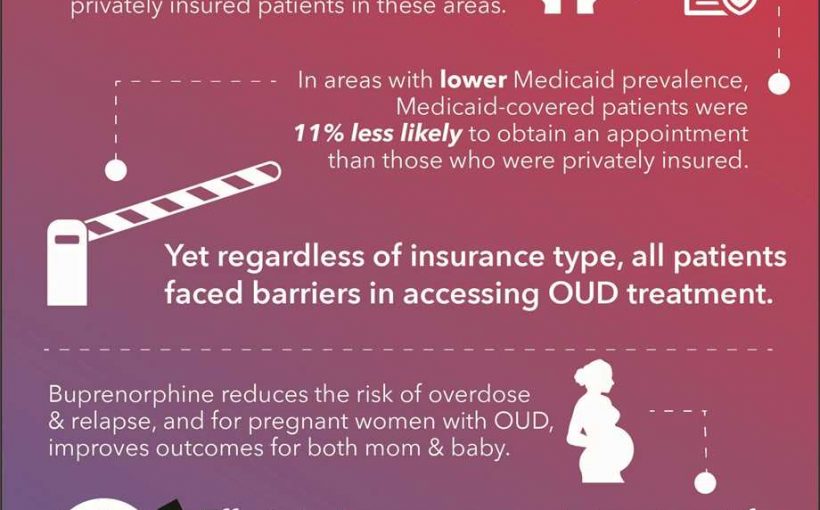

Buprenorphine is a prescription medication for OUD treatment that has proven effective in reducing the risk of overdose and relapse, as well as improving long-team health outcomes. For pregnant women with OUD this benefit extends to the baby—making it more likely an infant will be born at term and with a higher birth weight. Despite this, there continue to be disparities in access to OUD treatment.

In fact, despite a 300% increase in the number of clinicians who can now prescribe medication treatment such as buprenorphine, recent research finds that less than one-third of individuals with OUD received any form of pharmacotherapy within the prior year. Past studies have also shown significant disparities in access to OUD care when comparing Medicaid and privately insured OUD patients.

When looking at the new study’s entire sample of 3,420 calls to buprenorphine providers, the researchers found that less than half (45%) of privately insured women and only 38% of otherwise comparable women enrolled in Medicaid received an insurance-covered appointment.

When examining areas with lower Medicaid prevalence, there was an 11% difference, with Medicaid-covered callers being less likely to obtain an appointment. But as the share of the local insured population enrolled in Medicaid increased, the difference in access to care between Medicaid and privately insured callers decreased until the variance was insignificant.

While the underlying explanation for this equalization of care access for both populations is likely multifactored, the investigators speculate that because providers in areas with a higher Medicaid population are more familiar with the business processes needed to secure payment through Medicaid, they are also likely more open to accepting both payer types.

Because of the critical need to get this potentially lifesaving treatment to all individuals with OUD, the study’s authors suggest efforts to improve access to treatment are perhaps best targeted where Medicaid enrollment is lower. The group has additional studies underway to better define the barriers to care for individuals with OUD.

“Making it through the structural barriers to just getting into treatment for OUD is extraordinarily hard, even if you’re the most motivated person on the planet,” said study principal investigator Stephen Patrick, MD, MPH, director of the Vanderbilt Center for Child Health Policy. “We know these medications reduce risk of death, and yet it’s impossible for some folks to get into treatment.

Source: Read Full Article