Ever since I can remember, numbers have appeared to me in specific colors. The number 2 is baby pink, 3 is sunshine yellow, 4 is royal blue—the list goes on. It’s not just that they look a certain way, they are that color.

Consequently, whatever associations I have with that color carry over to that number. For example, I *hate* the number 7 for no other and no better reason than the fact that it appears orange to me, which I’ve always considered ugly. The color-number association is involuntary, which I know sounds odd, or even unbelievable. But it’s always been this way in my eyes.

I was 18 when I first learned there was a name for what I was experiencing: synesthesia.

I was reading a book in college for my freshman literature class, Speak, Memory, by Vladimir Nabokov (best known for his novel, Lolita). In it, he described how he saw letters in different colors and explained that he had synesthesia. I remember thinking, wait, there’s a name for this? Up until that point, I had no idea that seeing numbers or letters in specific colors was A Thing, much less a recognized condition.

My experience is one that Richard E. Cytowic, MD, has heard many times. “Synesthetes all tell the same story,” says Dr. Cytowic, who is a clinical professor of neurology at George Washington University and the author of four books on this topic (his latest is aptly titled Synesthesia). “They’ve always had it as far back as they can remember—they can’t remember not having it,” he adds.

He goes on to explain that most kids with synesthesia think everybody perceives numbers and letters like this (guilty). That is, until they ask a friend something like: “Oh, my ‘a’ is the most beautiful pink I’ve seen. What does your ‘a’ look like?” Almost always, the friend is confused and thinks the synesthete is out of their mind (we’re not). “Then, they [the synesthete] don’t talk about it because they’re ridiculed,” Dr. Cytowic explains. “So they assume that they’re the only person in the world with this and, then, finally they find out there’s a name.”

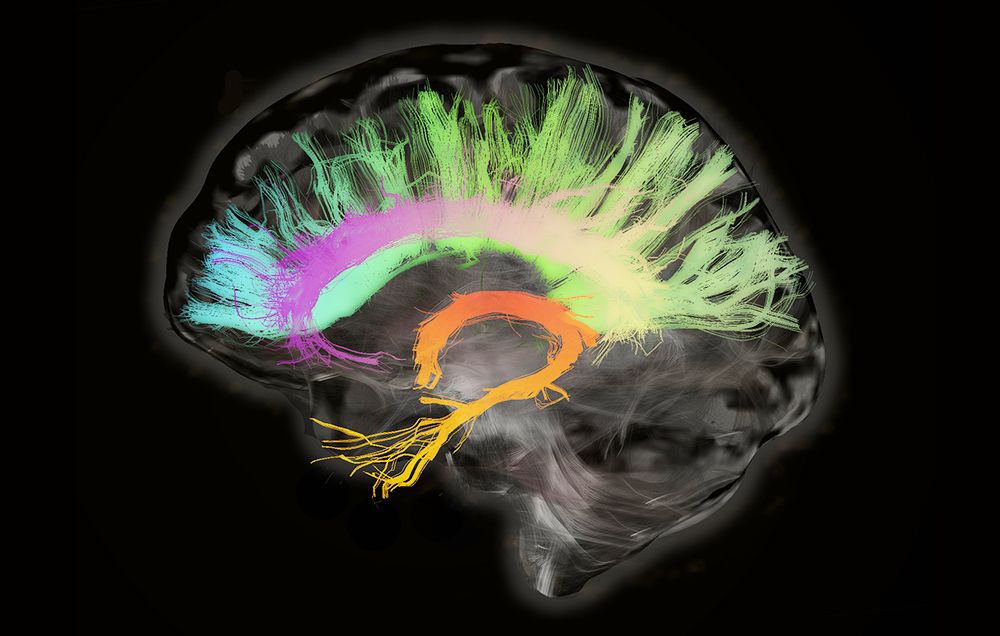

Simply put, synesthesia is when two “senses” are combined.

Quick vocab lesson: “Anesthesia” means “no sensation,” and “syn” usually means “joined or coupled,” says Dr. Cytowic. So, synesthesia essentially translates to “two or more senses joined together.” (The most intense synesthetes have all five of their senses hooked together, he explains.)

But, Dr. Cytowic is quick to add, “It isn’t really quite senses; it’s more than that.” The alphabet, numerals, time units, and calendar forms aren’t senses in the conventional sense, he explains, but they can all be included in different forms of synesthesia. Translation: While I see numbers in specific colors, others might associate colors with days of the week or months of the year. Or, others might taste a time unit (6:00 is bitter, while noon is sweet).

Jewelyn Butron

Jewelyn Butron

In fact, the most common type of synesthesia is sensing the days of the week as colored—Sunday is red, Monday is blue—followed by grapheme synesthesia, where numerals and other written elements of language are colored (what I have). There’s also colored hearing, where music and voices or environmental sounds, like a dog barking or door slamming, will cause photoisms. That might look like a colored, moving shape that arises, scintillates for a bit, then fades away (think: mental fireworks).

These are just a few of the dozens of synesthesia forms. But, however your synesthesia manifests, it’s “almost always a one-way street,” says Dr. Cytowic. “That means you go from sound to sight, but very rarely from sight to sound, or sight to smell.” (It’s not impossible, though, as there have been case studies on people with two-way synesthesia).

Genetics usually play a role in whether or not you have synesthesia.

“It’s inherited as an autosomal dominant trait,” Dr. Cytowic explains. (Basically, that means if only one parent carries the gene, you have the condition.) “It’s not a single gene, like the gene for whether you have blue eyes or brown eyes, so it’s highly heritable.” When he started studying families in the late 1970s and 80s, he found it running among multiple generations and in both sexes.

As for me, while this might sound silly, I don’t know if my synesthesia is genetic. I assume it is, but since I still keep my synesthesia mostly to myself (and tbh, don’t know if my parents are clued in to what’s going on upstairs in my mind). I wouldn’t be surprised if another family member had it and, like me, didn’t know it was an actual condition.

By the numbers: One in 23 people have the gene for synesthesia, but only 1 in 90 actually have some kind of synesthesia, he says. And while many people inherit the gene, it can also be a spontaneous mutation.

There’s thought to be some biological purpose behind the synesthesia gene.

For starters, it helps you remember, says Dr. Cytowic. For the average synesthete, like myself, it’s mostly good for memorizing more everyday things, like phone numbers. (Not to brag or anything, but I am pretty darn good at this.) It’s also likely the reason why (again, not to brag) I was the first person to memorize my times tables in second grade. Of course, when I tell Dr. Cytowic this and explain that, of course, I didn’t realize that may have been the reason at the time, he isn’t all that surprised. It makes sense: Even if I couldn’t remember the number, I could sense the color.

But Dr. Cytowic believes improving memory is far from synesthesia’s only purpose: “The short answer is that I and others think that this is the gene for metaphor,” he explains. “Metaphor, by definition, is seeing the similar in the dissimilar…and so, [synesthetes] are seeing similarities in variant superficially dissimilar things.” So, people with synesthesia may be more genetically predisposed to coming up with metaphors than the average person (no shade to my fellow writers).

Despite my career choice, that doesn’t mean I’m constantly coming up with poetic phrases. But I do find myself making a lot of connections to seemingly random things and old memories whenever I read a book, watch a TV show, or engage in some other form of content. It’s actually one of the reasons I have trouble listening to audio books; I’m reminded of something way out in left field and miss something.

Synesthesia might also help you unleash your inner ~artiste~. Even those who carry the synesthetic gene but aren’t overtly synesthetic will turn out to be highly creative people, Dr. Cytowic hypothesizes. “Synesthetes are represented among creative people—artists, musicians, novelists, painters—and even synesthetes who aren’t famous artists tend to be involved in creative endeavors,” he explains.

Wondering if you have synesthesia? If you do, you’d probably know it.

You don’t get diagnosed for synesthesia—at least, not in the traditional sense. A synesthete’s story is their diagnosis, explains Dr. Cytowic.

Because synesthesia is an idiosyncratic condition, you can’t just take a test, like a blood test or psychological test, to find out if you have it. “If you really want to prove that somebody has it or not, you have to invent a specific test to them—and this tends to be cumbersome and expensive,” he explains.

That might be something like a sensory test, in which you’d have someone tell you what color each alphabet letter or number is. “If you do this with a control group, have them memorize it, and tell them that you’re gonna repeat this [exercise] a week later, their performance is worse than chance,” Dr. Cytowic explains. “If you pull the same stunt with a synesthete, without warning—a year later or three years later—the matchup is pretty much spot on.”

Trust me, if I could change my synesthetic combinations to fit my aesthetic tastes, I would. But I can’t because I was **Lady Gaga voice** born this way. (Gaga is rumored to be a famous synesthete, btw.)

Sure, my synesthesia is not exactly normal, but it really doesn’t impact my life too much.

You’d think synesthesia would affect your mental health, but it really doesn’t (*insert massive sigh of relief*).

“As far as the health aspect goes, it’s usually parents who are worried that there’s something wrong with their children,” says Dr. Cytowic. “So they take them to see psychiatrists or developmental specialists.” The problem with that, though, is many doctors have never heard of synesthesia, so they might think this is the beginning of a psychotic episode, or that the child may turn out to be schizophrenic or something like that. “There’s a lot of unnecessary anxiety,” he adds.

In fact, the most common negative effect on your mental health, according to Dr. Cytowic, would be social embarrassment if/when you bring it up to others, and they look at you like you’ve just sprouted two heads, chicken feet, and—just for good measure—a dragon’s tail.

That doesn’t mean living with synesthesia is always easy, however. Two-way synesthesia, though rare, can be particularly difficult to manage, since you can easily become overwhelmed when you’re in an area where there’s a lot of stimulants (think: the colorful, bright, and busy Times Square).

But ultimately, synesthesia is “a wonderful trait to have,” says Dr. Cytowic. “People think of it as a gift, and they love having it.” (Yup, I can confirm.)

Often, when I explain what my synesthesia is like, people ask me if it’s annoying or distracting. But this is just my version of normal. As Dr. Cytowic puts it, synesthetes simply have a “different texture of reality.”

Most days, I barely even notice my synesthesia. It’s always there, and I’ve never known anything different. It’s my synesthesia’s world, and I’m just living in it.

Source: Read Full Article