“The book features birds from marshy wetlands like the Purple Moorehens, nocturnal birds like the Indian Nightjar, those commonly found in our urban cities like the Asian Koels, Magpie Robins, sunbirds, kingfishers and Jungle Babblers, among others.”

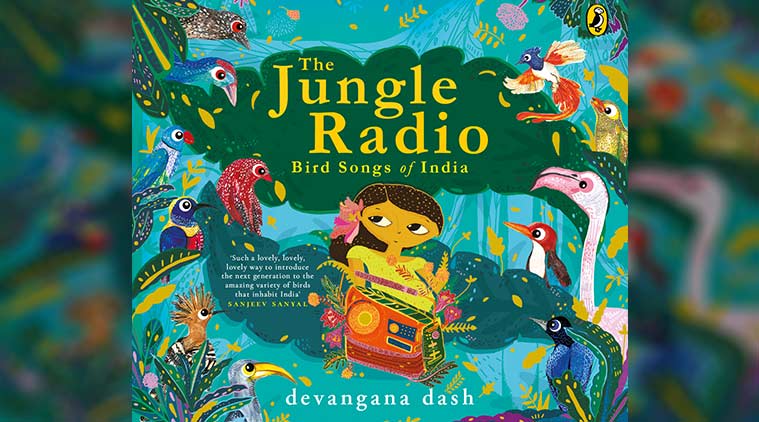

Devangana Dash, author and illustrator of The Jungle Radio: Bird Songs of India talks to us about the joys of picture books and introducing children to the joys of birdwatching.

What prompted the name of the book, The Jungle Radio?

It is a radio that you can read! When I was researching on birds in a protected forest area, I visualised the forest space to be one big acoustic space which contains so many sounds. There is always a sender and a receiver, and a multitude of sounds at different frequencies just like radio channels. Some birds are singing their intricately prepared song, while others are busy in their constant chatter and speaking like RJs. I conceived this nature’s rich choir just like a radio because of its element of musicality and the network of sounds it establishes. Also, one can carry this radio anywhere — you find these sounds in the cities, in your balconies and parks, in bird sanctuaries and in the dense national parks, away from the cities.

Why is it important to talk to kids about the birds and wildlife of India?

This book is a celebration of diversity in birds and their sounds, and is aimed essentially for urban children — to familiarise them with the myriad sounds around that we often miss or take for granted, and introduce them to the joys of birdwatching. Wildlife is often presented to be something ‘exotic’ and dwelling far, far away from our homes. I think that distance makes it not so relatable. We need more stories with an ecologically sensitive voice for children that encourage a young reader to wander outdoors, observe, imagine, ask questions, love nature and more importantly be a good listener to the world. Stories like The Jungle Radio are trying to call out to the fact that nature is all around us, if we look and listen carefully and we don’t have to go to faraway lands to feel closer to the wild. Nature sounds are in itself an important component of our natural resource and it is important to sensitise children towards them, as these sounds get lost amidst the noise of our city lives.

As clichéd as it sounds, children are the future of tomorrow and we have to make sure to make the world a better, safer place for them. I wrote and illustrated this book hoping to nurture an audience that is aware and sensitive in its engagement with wildlife and the natural world.

Tell us about your own childhood and if it inspired a love for nature.

I have always had interest in nature and wildlife. And grown up in a family that loves plants and animals. My father loves his plants and I have seen him meticulously nurture his garden every Sunday. And my sister has rigorously worked in the environmental conservation and her stories from her frequent field visits. I had the fortune of growing up in an ecologically aware household — where wasting electricity, water or bringing in polybags inside the house were real concerns. And I have always been a painter since childhood, painting lots of nature… flowers, plants, oceans, wild animals. I was born in a coastal place, and I was an ocean child. I still am!

So the nature lover in me was always there, but the student of nature in me was only properly introduced to this world in my adult life. Because of this embedded interest, in college I started seeking projects designed on themes of wildlife, nature and conservation. And these pathways led me to the birds and more of wildlife and I kept leaning towards more of these experiences that bring me closer to nature. I visited Bandipur national park and Salim Ali Bird Sanctuary through college, both a wonderland for bird lovers. I spent last New Year’s at a bird watching site in Chilika Lake, Odisha with my sister where you see thousands of migratory birds every year. This is how my interests and paths connected and everything came full circle, and I became a lot more sensitive to the world around me.

Further, the balcony at my Delhi residence attracts lots of birds like babblers, sunbirds, parakeets, kites, woodpeckers, barbets and hornbills, so I am used to being a patient audience to their songs and calls!

How close are the sounds you’ve spelt out in the book to the actual birdcalls?

It was slightly challenging to study sounds and phonetics and convert them into words. I referred to audio clips and recordings of bird songs and calls so I could accurately translate bird sounds into words, and still maintain the rhythmic, musical quality of the text. Field guides and writings on bird behaviour helped me in identification of the bird species and their calls. Some birds have a very peculiar call and are known for that, however there are others who have a variety of calls — these were the tricky ones! The sounds in the book have been classified depending on the behaviour and quality of calls of the birds. For example, the Hornbill always has a harsh, blazing call which I have described as that of a Trr-Trr-Trrumpettt!

I have put some birds in the same category, like the tweeting birds who have a clear, flute like voice come together in the book as three friends going tew-too-too, those are the Malabar Whistling Thrush, Scimitar Babbler and the Asian-Fairy Bluebird. Some birds were added as I heard them calling out in the Jungle, like the Greater Coucal—with a distinict goop..goop..goop sound that echoed through the forest the first time I saw the bird.

You’ve illustrated your own book. How important are illustrations for children’s picture books? How did you decide on the bright colours for The Jungle Radio?

As a visual communication designer and illustrator who works full-time as a book designer, visuals come to me first. So it was only natural to me to tell a story through illustrations, since I absorb the world around me through images and colours. Because it was an informative story on birds, the art played a big part in the story to enable bird identification and for children to memorise the species.

Pictures are a very powerful medium of storytelling and human memory grasps pictures faster. For a child who is yet to develop a reading habit, picture books are an introduction to the experiences yet to be discovered by them. They broaden a child’s imaginative canvas and the bright colours, variation in lines and shapes, the layered characters, everything comes together to create a small world functioning within the book. Children are inherently creative, and they might make a completely different meaning of the pictures they see in a book, which is why picture books are also open to a lot of interpretations and don’t usually end with a prescriptive, moral of the story. Which also makes them popular across age groups, and loved by adults too, and they never go out of trend because they are relatable, and always full of art.

I feel picture book artists have a fun, but very responsible task at hand — of telling the world through pictures, on important subject matters. It’s so great to see Indian picture books getting popularity, and so many Indian publishing houses dedicated to bring in new and exciting content for children through picture book makers.

The world of birds is extremely colourful! And colours play a significant role in their identification and nomenclature — black rumped, blue throated/bearded, white breasted, violet backed, yellow wattled, rose ringed etc, are all names of specifies derived from their colours. Hence, it was predetermined for this book to be this colourful. I conceptualised the colour palette of the pages to suggest that Gul, the protagonist, spends one entire day in the jungle. The 40-page picture book starts from the mellow sky blues of early morning, goes on to the afternoon yellow ochres, to the salmon pinks and oranges of dusk, and lastly the deep magical violets of nightfall. Some white pages in between, are inserted to balance the lushness of colours. In this way when you are walking through the jungle from page to page, you are on a colour ride and see an evolving colour-scape. This was my colour philosophy while art directing the artworks for my book.

How did you pick the birds featured in the book? Which parts of India do they cover?

A total of 30 Indian birds were selected to feature in the book to ensure diversity in colours /appearances, regions, behaviour and calls. During the selection I ensured these set of birds cover most regions of the Indian subcontinent in terms of where they are usually spotted or migrate to. Some birds were native to certain regions, whereas others are more widespread. I obviously wanted to add many more birds to do justice to the distribution, but had to keep in mind that the story doesn’t get too long, since it is primarily for a young age group. Apart from the geographical and ecological classifications of these birds, the prime factor in their selection was the sounds they make.

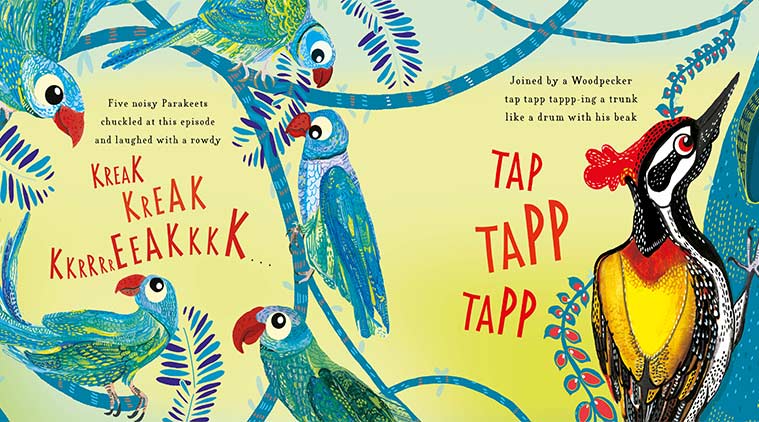

Some bird characters feature in the story because of their unique quality of calls — song birds like the Whistling Thrush and the White-Rumped Shama, to duet singers like the Bee-Eaters, group callers like the Jungle Babblers, and even drummers like the woodpecker. Some talking birds like the Brainfever bird to mimics like the Black Drongo, and also those which have a distinctly loud and harsh voice like the Malabar Hornbill.

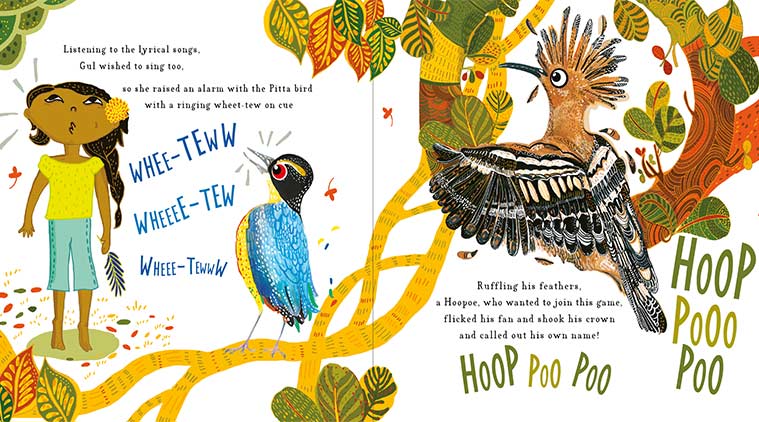

I tried to showcase birds from different types of habitats, those dwelling in the evergeen, or scrub jungles, coastal regions and grasslands. The Jungle Radio features birds from marshy wetlands like the Purple Moorehens, nocturnal birds like the Indian Nightjar, those commonly found in our urban cities like the Asian Koels, Magpie Robins, Sunbirds, kingfishers and Jungle Babblers. I also introduced some birds to inform kids about certain sub-species, like the Grey Malabar Hornbill and Malabar Parakeets — species native to the Western Ghats. I tried to include not-so-common birds like the Indian Pitta — a tiny bird who has nine colours on its body, breeds in the Himalayas and migrates larges distances to the rest of the country. It’s call is a spectactular, nasal whee-tew. Birds like the Indian Roller or the Neelkanth were selected because of their acclaimed status. It is the state bird of Odisha, Karnataka and Telangana and popularly associated with Lord Vishnu and Shiva. Another extremely fascinating bird for me is the Eurasian Hoopoe, who could have been a part of the book only for its guest appearances because of its flamboyant crown of feathers. The bird has so many native, indigenous stories attached to it and features in folk tales across the world. I call that bird an international rockstar!

What age group is the book aimed at? How would you like a child to read it?

The book is essentially for a 4+ audience. Even if a tiny child cannot ready full sentences, they can always identify the birds through the illustrations. The format of the picture is a large square size, so the big artworks are easy for a young child to browse. On the first page, I have given an introductory note on how to read the book. Apart from the narrative, there are big, colourful sound words in capital letters, placed next to the artwork of the bird. A young child can easily read them out with the help of a parent/educator and learn the sounds. I definitely want the reader to engage with the book and call out the sounds loud! Which is also why the text has a slight sing-song quality to it and follows a rhyme scheme. There are certain action birds like the Indian Pitta, who lifts its entire body and screeches its nasal call! Gul, the character in the book also interacts with the birds at various points in the book — she is talking to the birds, standing on her toes to sing along, asking questions.

The entire narrative was woven to make this super interactive and enjoyable for a child. Some mothers have been sending me videos of their children reading The Jungle Radio and it is heartwarming to see the kids tuning in to the radio with their songs. Next time they hear a particular sound of any of the birds from the book, I hope they get excited and can recall the singer. The idea was to encourage young birders, which is why the last few pages in the books have some tips to become a birder, some great sites to spot birds in wild, as well as an identification chart with all birds in the book. Through the book, I have tried to translate the science of birds and their calls into a more interactive, accessible and enjoyable story.

How can parents ensure their kids stay connected to nature? Which are the top bird watching places you would recommend?

Take them outdoors more often! To the parks, and to the birdwatching sites. Let them stay more in touch with the ecosystem around them. Only when the young generation is aware of the natural world around them, aware about what are we losing and what is in excess, will they be sensitive towards it and be mindful to protect and value it. Nature teaches us so much. Let the children be inspired by nature in their art — when they paint different kind of leaves, trees, flowers, birds, they learn so much about forms and shapes and colour.

There are national parks and protected areas spread across our country, and the last page in The Jungle Radio book has a tiny list of the sanctuaries you can visit to spot birds and more of wildlife. Most of these places are extremely accessible like the Okhla bird sanctuary, nestled around a metro station just 3kms away, and is known to have over 300 species of birds. Also, the best thing about being friends with birds is that they are everywhere! You can sit for hours just listening to them, observing their mischievous tricks and strategies. They become an extremely interesting subject to study because they are always around us. You just need to head out to your balcony or terrace and there you see a myna or a kite! You see so many of them in the cities. Through this book, I hope I am able to involve children to observe birds more and listen to them and appreciate their existence and the beauty and musicality they add to the world around us.

Source: Read Full Article